After many years of setting up projects for our industrial designers and mechanical engineers, here are my thoughts on some basic best practices on how to structure your files and keep your project organized. We’ll concentrate on the importance of Pack-and-Go’s in this segment. This is a very important set of practices that will help keep you out of trouble. These concepts are important even if you have a PLM system, because it helps you understand how the PLM helps keep you organized.

Good morning. My name is Montie Roland. I’m with Montie Design in Morrisville, North Carolina.

And this morning what’d I’d like to talk about is how to structure your project from a file standpoint, from an organizational standpoint.

Montie Design is a full-service design firm in Morrisville, North Carolina. We provide industrial design, mechanical engineering and prototyping capability on-demand to help you move your project from concept to ready-for-the-shipping-dock.

The Concept directories are where you’ll store your sketches, your ideations, maybe your solid model concepts, pictures for your style board. So then, when you think about these files we’re starting to store, you really have two types of files. One type of file is parametric, and the other type of file is static. And then really . . . I guess a third file would be like a . . . a file that’s directly editable. When it comes to Cat files, though, we have two types.

So, parametric files are files that are linked or potentially linked to other files. This is very, very important to keep in mind. So, with Solid Works, we can save a non-parametric file to a format like STEP or DXF or IGES or DWG or PDF. These non-parametric files can be edited, like, easily in the case of DXF or DWG; less easily in the case of PDF. And so these files, though, are generally not going to change just because you changed something somewhere else in the Solid Works model. However, the Solid Works files from Solid Works are parametrically linked in many cases. So, for example, a drawing file is going to go reference the part file to rebuild the drawing. So, if the part file is missing, it can’t reference it and can’t rebuild drawing and get a, basically, a blank screen in the middle of your . . . your drawing. So this is very, very important to keep in mind. Whenever you move files from one directory to the other (and occasionally you need to do this anyway), you run the risk of orphaning a file that’s somewhere else. So a good example of this is . . . let’s say I’m working on (in Solid Works) and I got to McMaster Car and I download a screw (which is a great way to get a screw). So, I download that screw and then I open it up; it comes across as a STEP or an IGES, and then I import it into my model. And when I hit “save” that McMaster Car Screw was saved to my download directory on my local machine. So, if I don’t consciously save that to my Current Design file . . . Current Design directory on the server, then . . . or on the Z-drive, then what’s going to happen is that now I have files in two different places. So, if I was to go and grab Current Design and move it into Release, let’s say. Just copy it over. I would leave that screw behind. Because the copy tool in Windows Explorer does not know about the relationships in Solid Works. So, it doesn’t know to go grab that.

Solid Works has this wonderful utility called “Pack and Go”. Pack and Go finds every file that’s linked to the files that you have open. So, what you want to do is go to the top level of, let’s say, Drawing. Or top-level Assembly. Open up Pack and Go, and then it’ll give you some options. And, generally, you want to exercise all those options in terms of including drawings, including . . . textures, including decals, FEA results; grabbing all that’s good – that way you don’t leave something behind. Solid Works will go look for those files, make a list of them, let you see that list, and then you pick a location where you either want to save that as a zip file, or you want to save that . . . just to that directory; drop the files in that directory. So, you choose that directory and then you hit “Okay”. Then Solid Works will think, and then it will start grabbing files and copying them to that directory. If you do not do this, it will bite you. It is not a question of if it will bite, it’s a question of what moment, what day, and how bad. Because we’ve seen this before. You can imagine that if you have files on a local machine and you just copy them over, or you copy them between places on the Z-drive or what have you, and you orphan some of these files, it can be very painful to find those, get those back. And then you’re never really sure you have the right one. So, let’s say you orphan a single screw. Okay. Worse case, you go download it from McMaster again. But let’s say that you have somehow ended up with a part file that’s in an unknown Rev (or even if we know what the Rev should be) and maybe it’s in some directory. It can very easily happen that you inadvertently saved it to the wrong directory. So, maybe you’re working in Current Design but you’re using a file from Rev 02. But that file is actually Rev 07. So, you grab the stuff out of Current Design, move it to Rev 08. You missed the Rev 07 file. Well, now, all of a sudden, we’ve got no clue where to find that file. And it’s difficult to find without pulling up every single file in . . . on the . . . in the subdirectory on the Z-drive and on your machine, and try to figure out which one it is. And even then, we’ve got to go by the Revision number and properties. And that’s just painful because that still doesn’t tell us it’s the right one. Because there could be, like, a 7 there and an 07 here and which one’s the correct one.

If you do Pack and Go, you avoid soooooo much of that trouble. It’s . . . Pack and Go is your friend. I just . . . this is one of those things that’s important to emphasize.

So, a similar thing applies to other programs. For example, PowerPoint has a Pack and Go feature; use it. Grab all of these images, put them in a Pack and Go file, because that . . . most of the time when you’re working on projects, you end up with images in different subdirectories. It’s on a local machine. It’s on a . . . it’s on your network. But if you do Pack and Go it grabs all those and puts them in the same space. Yes, you use more disk space. I’ll argue that disk space is dirt cheap compared to a few hours of looking for a file you can’t find ten minutes before your deadline.

The same goes for . . . you know, you’re working in an Adobe product. If you have the option to embed it in the file rather than link to it – embed it in the file. I realize this can make your . . . catalog a gigabyte in size. But, it’s so much better than two months’ later pulling it up and missing files. There again, disk space is cheap; time’s not. So, embed those files. Pack and Go. You know, use these features in these programs so that it makes it easier.

Alright, so, it’s also important to note that you have a PLM system, and you do check-ins and check-outs. It’s going to be a little different because that software is going to manage a lot of what we’re talking about. So, I’m not . . . I not sure. I think it’s beyond the scope of this podcast to go in depth on . . . on the PLM systems. But, they’re great. They’re awesome. They help manage some of those. So, in this case, we’re just talking about the manual.

But, on the other hand, if you understand the manual, it makes it a lot easier to understand the PLM.

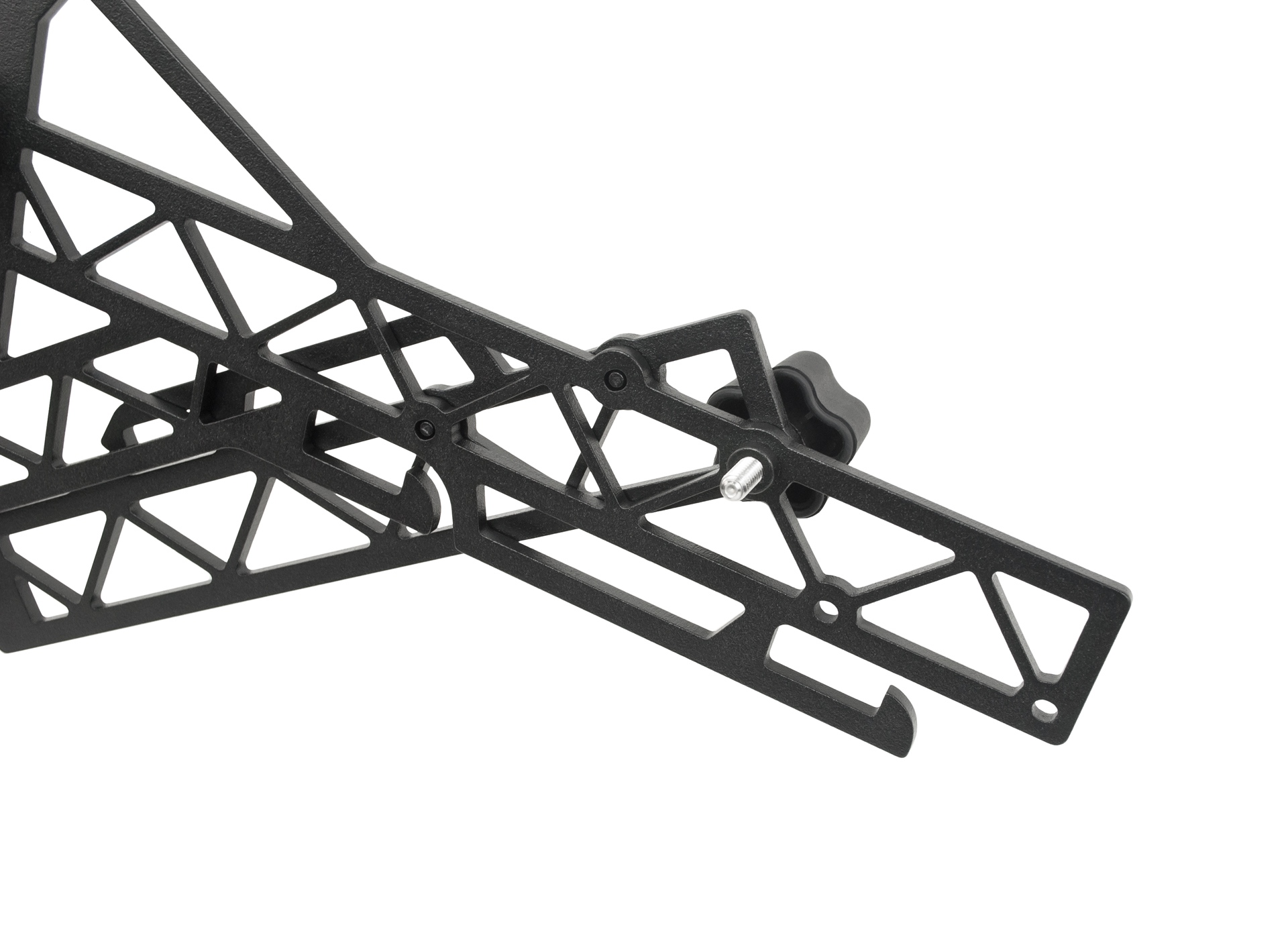

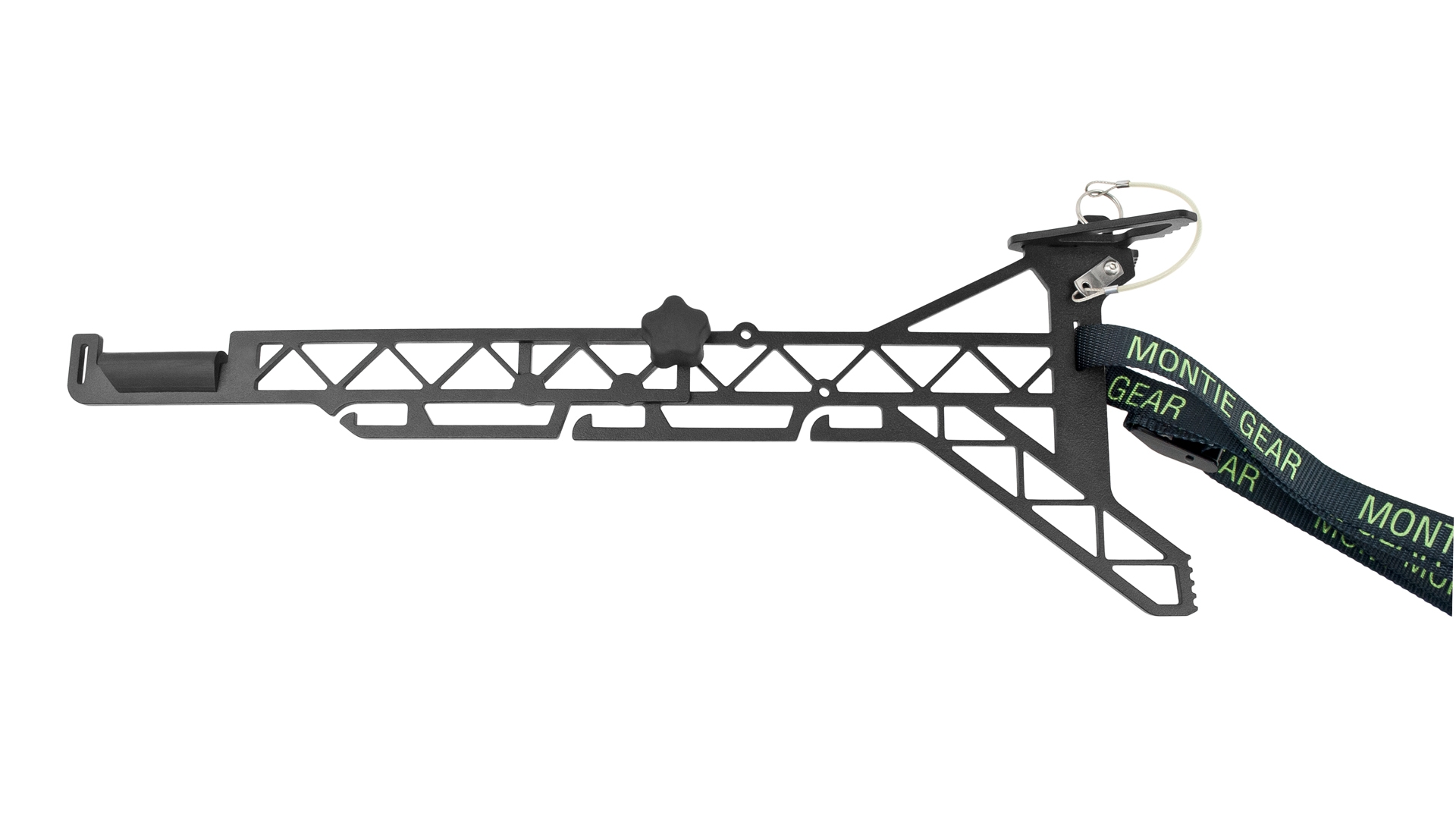

If you have any questions about this, please don’t hesitate to give me a call. I know it’s kind of a long section here and technical, but happy to entertain your calls, questions. It’s 1-800-722-7987. That’s Montie Roland. Email – montie (M-O-N-T-I-E)@montie(M-O-N-T-I-E).com. Or you can visit our website – www.montie.com. You can see the results of client work we’ve done at the montie.com website. Or you can see some of our projects that we’ve done for ourselves at montiegear (M-O-N-T-I-E-G-E-A-R).com.

I hope this has been beneficial. Montie Roland, signing out.